A Student's Guide to Looking After

Your Mental

Health at University

Brought to you by:

An

introduction to

mental

health for

students

Going to university is an exciting time, but the change it brings can be overwhelming. Moving away from home, making new friends and being responsible for your own learning – it’s a new sense of independence for many.

It’s important to look after your mental health throughout your years studying, because that freedom can present challenges.

What is mental health?

Everyone has mental health. It affects how we think, feel and act. It is influential throughout our lives because it determines not only how we feel about ourselves, but how we interact with others and the choices we make.

Good mental health allows us to:

- Realise and fulfil our potential

- Work productively

- Making meaningful contribution

- Maintain happy relationship

- Cope with stresses of life

Mental health affects how we deal with challenges and approach tricky situations. This is when many people might notice they’re struggling, because of the additional stress.

A certain amount of stress is inevitable, but we all deal with it differently. When our mental health affects our ability to function normally, it becomes a mental health problem. This could interfere with your everyday life. Some of the most common mental health problems include:

- Anxiety and panic attacks

- Depression

- Eating disorders

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Bipolar disorder

- Psychosis and schizophrenia

Why are students vulnerable?

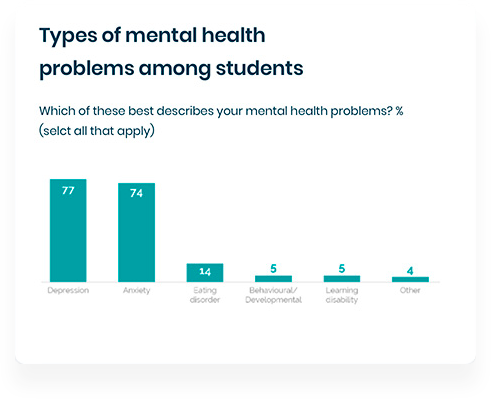

One in four students suffer from mental health problems, according to a new YouGov survey of Britain’s students. Although mental health problems can be caused by a huge range of issues, and vary between individuals, university presents a unique environment which has the potential to be damaging.

According to Mind, research shows many people first experience mental health problems or first seek help when they’re at university. The mental health charity explains that some of the things which make students susceptible include:

- Age Research shows 64% of the university student population are between 16 and 24 years old. This increases to 83% when just looking at the undergraduate population. This age group is particularly vulnerable to mental health issues, with 75% of problems established by the age of 25.

-

Stress Stress isn't a mental health problem, but

it can contribute to issues. Unfortunately, becoming a student can be a stressful

experience for many. The YouGov survey found the primary causes of stress among students

are:

- Work from university (71%)

- Finding a job after university (39%)

- Their family (35%)

- Jobs (23%)

- Relationships (23%)

- Friends (22%)

Other studies raise the potential stress from: managing your own finances, health issues, student life not living up to expectations, living conditions and trying to fit in.

- Lack of support. A lot of students move away from home to go to university. This means leaving your family and friends – your typical support network.

The unique situation for university students

Even if it’s exciting, change isn’t always easy to cope with. Challenges which students probably haven’t faced before include:

- Being away from home and living with new people

- Maintaining relationships with family and friends from home

- Managing your own time and responsibilities

- Meeting new people

- Dealing with deadlines and exams without teachers regularly checking in

- Pressure to succeed

- Uncertainty about employment after graduating

- Managing finances

Advice on adjusting

to university

life

When you’re searching for a suitable university, it can feel like starting your course is a long way off. But the summer goes quickly and, before you know it, it’ll be freshers week. To ensure your first few weeks aren’t overwhelming, there are some important tips to remember:

-

Prepare during summer

Secure accommodation. Buy your books. Research the town. Get pots and pans. Do all of the things you can to get ready for moving out. If you leave it until the last minute, it could be a stressful rush to prepare for your first week.

-

Learn some basic recipes

Talking of pots and pans, you’ll be cooking for yourself while you’re living away from home. If you’re not a keen cook, it’s worth testing out a few basic recipes so you know what you’re doing. Try and get some vegetables in there too.

-

Expect some nerves.

As the time draws closer, it’s natural to be nervous. Remember all students are in the same boat. They’ll be experiencing similar feelings, so you’re not alone.

-

Give yourself time to chill out.

In the first couple of weeks, you’ll be quite busy with freshers week and course introductions. But make sure to give yourself some down time. It’s important to relax, so take time to catch up with your friends and family, watch a film or exercise – whatever you enjoy.

-

Find people you get on with.

It’s nice to enjoy things with other people too. To maximise your chances of meeting other students you’ll click with, you should look into clubs and societies relevant to your interests. They usually hold introductions at the start of the term, so plan ahead.

-

Don’t feel pressured into things

In a new environment and with new people, it can feel like you have to do things to fit in. Just remember you shouldn’t do anything that makes you feel uncomfortable.

-

Learn to plan your time.

One of the biggest differences about university life is how much freedom you have. You’re in control of your own time, so it’s useful to learn how to schedule and prioritise. Set aside time for university work, socialising and relaxing.

Looking after your mental health

Student life is busy, with lectures, seminars, societies, a social life, and maybe a part-time job to balance. Because of this, looking after yourself can often come low on your list of priorities. It’s important to take care of your wellbeing – including your mental health.

Good mental health allows you to work in a productive way, juggle the different commitments you have, and enjoy spending time with your loved ones. It also helps you cope when life gets busy or stressful.

According to the Mental Health Organisation, “early interventions and home treatment for mental health problems can reduce hospital admissions, shorten hospital stays and require fewer high-cost intensive interventions.” Not only does early recognition of a problem help the person to deal with it quicker, but it can also save the health sector up to £38 million per year.

How to spot if you’re struggling

It might not always be obvious something is wrong – or you might feel a bit ‘off’ but not be able to identify what the problem is. Although mental health conditions have different characteristics, there are some common symptoms that indicate poor mental wellbeing

Look out for:

- Feeling low most of the time

- Constant worrying or anxiety

- Irritability, moodiness, and a shorter temper than normal

- Inability to focus

- Not enjoying activities you normally like

- Finding everyday tasks (such as cooking and showering) difficult

- Lack of appetite

- Lack of energy

- Sleeping too much, or not sleeping enough

Support available

Support is available from different sources, both at your university and outside of it.

University wellbeing services

Most universities will have a student wellbeing service that encompasses all aspects of health, including mental health. Your university may provide its own free counselling service, for example, or a mental wellbeing team.

The 2018 Times Higher Education Student Experience Survey asked participants to rate their universities on their welfare support, and how their personal requirements were catered for. Harper Adams University received the best rating, followed by Loughborough University and the University of Chichester.

Helplines and charities

It can be difficult to speak to someone about your mental health. Some prefer to talk to people they don’t know personally, which is where helplines come in. You can also visit the resources on mental health charity websites.

Samaritans

You can contact the Samaritans helpline anytime – they are available 24 hours a day, year-round, providing non-judgmental support to people who need it via phone or email. Everything you tell them is confidential and it’s free to get in touch.

Despite their name, they are not a religious organisation and you can contact them no matter what your beliefs are.

Phone number: 116 123

Email: jo@samaritans.org

Mind

Mind is a charity that provides support and information about mental health, including different types of mental health problems, guides to everyday living, and a list of support and services.

You can contact their infoline to get information about the support available in your local area. It’s open from 9am-6pm, Monday to Friday, except on bank holidays.

Call: 0300 123 3393

Text: 86463

Email: info@mind.org.uk

Seeing a doctor

Making an appointment with your doctor can be a big step forward. It might feel daunting to discuss your mental health with a medical professional, but appointments are confidential and there are a number of ways your GP can help you:

- By answering their questions, you may start to understand what you are experiencing, and they will be better placed to provide the help you need.

- They can refer you for talking therapy with a qualified practitioner.

- They may suggest prescribing medication to ease your symptoms.

- They can identify changes you could make to your everyday life.

Before your appointment, write down your symptoms and any other information you think the doctor needs to know, such as stressful events from your past or present, or any family history of mental illness. Even if you find it difficult to explain your situation out loud, you’ll have something to show them.

Don’t be afraid to ask your GP questions about the information they give you, or the treatments they suggest for you. You can make a note of their answers if you think it will help you remember.

Did you know?

30% of GP visits are related to mental health source

Talking therapy

Talking therapy involves discussing your thoughts, feelings, and behaviour with a trained professional. They can help with several different issues, such as:

- Difficult emotions, including anger, confusion, and low self-esteem

- Difficult life events, for example losing a job or a loved one

- Mental health conditions like depression and anxiety

- Relationship problems with a partner or relative

- Traumatic experiences

There are different types of talking therapy, including:

- Cognitive behavioural therapy, which explores your thoughts and how you can change your behaviour in relation to them

- Dialectical behavioural therapy, which looks at opposite positions (such as two very different emotions, for instance) and how they might exist together

- Psychoanalytic therapy, which aims to identify deep-rooted thoughts that stem from childhood

- Solution-focused therapy, which focuses on solutions for the future, rather than looking at the past

Many therapists are trained in more than one technique and will adapt their approach according to your individual situation.

There are several factors that determine how useful you’ll find talking therapy: whether or not you trust your therapist, what you want to get out of the sessions, and how you feel about therapy in general.

Many people think of therapy as something you only do once you’ve reached breaking point. But it’s worth trying even if you feel like something isn’t quite right. It can help you understand your thoughts and behaviour better, which in turn can help you cope with any difficult situations that arise in future

Medication

Medication can be prescribed to help ease the symptoms of mental health conditions. There are four main types of psychiatric medication.

| Type of medication | What it does |

|---|---|

| Antidepressants |

As the name suggests, antidepressants can treat depression, but they are also prescribed for other conditions, including anxiety, phobias, OCD, PTSD, and eating disorders. They work by prolonging the activity of specific mood-regulating chemicals in the brain. Changing your brain chemistry can lift your mood. There are different types of antidepressants, including SSRIs, SNRIs, MAOIs, and tricyclics. They have similar effects, but may have different side effects. |

| Antipsychotics |

Antipsychotics treat mental health conditions where the symptoms may include psychotic experiences, such as schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, some types of bipolar disorder, and severe depression. They work by reducing and controlling symptoms, which helps you feel more stable in day-to-day life. There are two main types of antipsychotics: first generation and second generation. |

| Mood stabilisers |

Mood stabilisers are part of the long-term treatment for bipolar disorder, mania, hypomania, and recurrent severe depression. They stabilise your mood if you suffer from extreme highs or lows. Mental health specialists can prescribe mood stabilisers, but regular GPs cannot. |

| Sleeping pills and minor tranquillisers |

Sleeping pills and minor tranquillisers are prescribed to people who experience anxiety or sleeping problems. (Some people may experience both.) They are sedatives, which means they slow down your brain and body’s functions. They can reduce feelings of agitation and help you feel more calm and relaxed. |

(source Mind)

There is still some stigma surrounding medication for mental health. However, medication can treat many of the physical symptoms of mental health, and lots of people find it to be a great help. Reducing these symptoms enables them to carry on with their lives as normal.

Think of it this way – you wouldn’t expect someone with a physical illness or injury to heal without medical treatment. Mental health conditions are the same. There’s no need to be embarrassed if you need to take medication.

Luckily, research shows attitudes towards mental health problems continue to improve. In the most recent Mental Health Network factsheet, 65% of respondents were willing to state someone they were close to had or has a mental illness, compared to 58% five years prior.

Tips for maintaining a healthy lifestyle

A healthy lifestyle can’t cure a mental illnesses by itself. But we all know drinking plenty of water, eating a balanced diet, getting regular exercise, and getting enough sleep are good for us. Taking care of yourself can be difficult when you’re struggling with your mental health, however, so here are some tips for maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

Drink plenty water

We’ve all heard the theory that we should drink eight glasses of water per day to stay properly hydrated. However, it depends on your individual needs – the NHS currently recommends drinking between six and eight glasses per day (more in hot weather).

Staying hydrated improves your concentration and brain function, improves digestion, and can prevent fatigue and headaches from developing.

Eat a balanced diet

As a student, you’ll be sticking to a strict budget. This doesn’t mean you can’t eat well – you just need to be savvy when it comes to your weekly food shop.

Here are some of the best tips

- Buy frozen fruit and vegetables. You get more for your money, they’re often pre-prepared, and they’re just as healthy as the fresh versions, if not more so, because freezing seals the nutrients.

- Look for the cheapest brands. Supermarket value brands are often just as good as branded items, but with a much lower price tag. The least expensive products are often on the bottom shelf, so don’t forget to check. Shopping online? Just select the ‘Price low to high’ viewing option on each category page.

- Add pulses like beans and lentils to your meals. They’re high in vitamins and fibre, and bulk out dishes like chilli, curry, and fajitas. You could even experiment with using them as a meat replacement.

- Get creative with your leftovers. Blend vegetables with some stock to make a soup, eat yesterday’s curry in a wrap, or serve your pasta as a cold salad.

Meal planning

Planning most of your meals in advance means you’ll only buy what you’re going to eat. It can be difficult to buy the right amount of ingredients when you’re only shopping for one person, so consider cooking extra portions in the evening and saving them for lunch the next day. You can also keep some meals frozen.

The cost of impulse buys can quickly add up, so make a list before you hit the supermarket and make sure you’re not shopping on an empty stomach. It’s a lot more tempting to put extras in your trolley when you’re hungry.

Don’t forget to browse online for cheap, healthy recipes.

Drink alcohol responsibly

Alcohol is a depressant. This means it can alter the balance of your brain chemistry, which has an impact on your thoughts, feelings, and actions. This means it can also affect your mental health.

You might feel more relaxed at first. This can lead to increased confidence levels, and encourage you to drink more. However, the more you drink, the more likely you are to feel angry, anxious, or even depressed.

Alcohol can be hard to avoid when you’re a student. Not everyone chooses to drink, but if you do there are ways you can enjoy yourself more responsibly, like making sure you eat a big meal before you go out and alternating between alcohol and soft drinks. Never let your drink out of your sight in case someone interferes with it.

Get regular exercise

Exercise isn’t just good for you physically – it’s a huge mood-booster. It releases endorphins, chemicals in your brain that make you feel happier and more energized. It can also reduce inflammation in your brain, relieve stress and tension, and help you focus on something other than your worries.

And you don’t just have to go to the gym. Any kind of movement is beneficial, whether it’s playing on a sports team, taking a yoga or pilates class, or trying an outdoor activity like hiking. Find something you enjoy doing and you’re more likely to make it part of your routine.

Sleep well

There isn’t one amount of sleep that’s right for everyone – some people need more than others, even once they reach adulthood. However, as a general rule, The Sleep Council recommends adults between the ages of 18 and 65 get between seven and nine hours of sleep per night.

Mental health conditions can often cause sleep disturbances, which can be frustrating. Getting good quality sleep can significantly improve our well-being. However, there are some basic techniques you can use to set yourself up for a better night’s sleep:

- Make sure your bedroom is cool (but not cold), quiet, and dark.

- Avoid looking at electronic devices like laptops, phones, and tablets at least an hour before you go to bed. If you can’t quite give them up, consider installing a programme that limits the amount of blue light emitted by your device – it’s this light that tells your brain to stay awake.

- Identify what makes you feel most relaxed. Is it a warm bath or shower? Reading? Stretching? Dim the lights and spend an hour or so winding down before you attempt to fall asleep.

You could also try the Sleep Council’s 30-Day Better Sleep Plan to get personalised suggestions.

How to support other students

Advice on shared living

University accommodation varies. You might get your own bathroom, or you might have to share a bathroom and kitchen with strangers. The amount of people sharing will vary too.

Some universities don’t have enough accommodation for their undergraduate intake, so you could find yourself in shared private accommodation. Either way, it can take some getting used to living with other people.

Some of the best things you can do include:

-

Set up a budget for household essentials

You won’t need to buy multiples of basic essentials that everyone uses. This includes things like washing up liquid, bin bags, hand soap, and toilet roll. Setting up a small monthly budget means it doesn’t always fall to the same person to buy stuff.

-

Organise chores

These will never be split equally (some people are more bothered about cleanliness), but it’s important everyone chips in. Decide at the start whether everyone will be responsible for their own washing up, or you’re going to take turns. For other shared areas, you could set aside time to clean as a group or even decide to pay for a cleaner. It sounds silly, but a lot of arguments are caused by messy houses.

-

Spend quality time together.

It’s better for everyone if you get on with the people you live with. Rather that relying on the time you have to spend together, dedicate time to go out and get to know each other away from the house.

-

Decide how you’ll pay for bills

This will only apply if you’re renting private accommodation (as bills tend to be included by universities), but make sure you arrange how you’ll all contribute to monthly bills early on.

You just need to be considerate of others and you’ll get along with most people. Take food, for instance. The last thing you want after a long day at university is to come home and find your food has been eaten. It’s bound to cause issues. When sharing space with other people, you’ve got to consider how they feel too.

How to talk to others about mental health

If anyone opens up to you about their feelings, the most important thing for you to do is listen. Don’t assume you know how they’re feeling; ask questions and take them seriously without casting any judgement.

Similarly, if you think someone is struggling, you should ask. University is a major life transition and there’s naturally a lot of adjustment to talk about.

But it’s important they feel comfortable talking to you. Sometimes it can be easier to start a conversation with a text because it can be tough at first. Once people begin to share, it can feel like a big relief. 2 in 3 people report having experienced a mental health problem in their lifetime, according to the Mental Health Foundation. You might not even be aware someone is struggling, until they open up.

If someone talks to you about their mental health, it’s recommended you:

-

Make yourself available.

Try and make it clear you have time to talk. Make sure there aren’t any distractions. And check in after the initial conversation too.

-

Don’t belittle any feelings

Avoid saying things such as ‘you’re just having a bad week’, because it can make someone feel like you don’t take them seriously. Similarly, don’t say anything judgemental or try to second guess their feelings.

-

Don’t pressure them to share

Let them control how much or how little they talk about.

-

Don’t gossip

How someone else feels shouldn’t be something you talk about with other people casually. It takes courage to discuss your mental health with another person; show them they can trust you.

-

Focus on them

Try and make it clear you have time to talk. Make sure there aren’t any distractions. And check in after the initial conversation too.

-

If you don’t understand, do some research.

Don’t worry if you don’t have all the answers. You can look into what you’ve been told and continue to listen. If you have any doubts, ask them how you can help.

-

Offer them help seeking professional support.

You could offer to go to their GP with them, or find help available online. You may feel that their problems are too serious for you to help with

When to ask for help

NHS advice reinforces the message that “it’s normal to feel down, anxious or stressed from time to time, but if these feelings affect your daily activities, including your studies, or don't go away after a couple of weeks, get help.”

If you – or anyone around you – is struggling with the following feelings for a prolonged period of time, the NHS says it’s time to get help:

-

Signs of depression and anxiety

- Feeling low

- Feeling more anxious or agitated than usual

- Losing interest in life

- Losing motivation

-

Some people also:

- Put on or lose weight

- Stop caring about the way they look or about keeping clean

- Do too much work

- Stop attending lectures

- Become withdrawn

- Have sleep problems

How to support other students

Universities have varying policies on what classes as ‘mitigating circumstances’, but if anything is impacting your ability to complete your work on time or to your usual standard (including mental health), then you can apply for extenuating circumstances for the exam or coursework you think it’ll affect. You could get an extension or special arrangements made for an exam (e.g. not having to sit in a busy exam hall).

It tends to be assessed on a case-by-case basis, so the best thing you can do is to speak to someone in charge of your course or the university’s advice centre. They might say you need evidence – for example, a note from a GP or counsellor. But don’t worry if you haven’t asked for professional support yet. You still have a reason to speak up.